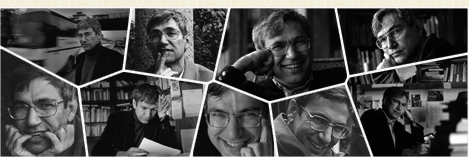

Robert Carver ..meets the Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk and discusses astrology, war, identity and east-west relations..

Let Constantinople in Tiber melt

A ship sailing between Venice and Naples in the seventeenth century is captured by the Turkish fleet. A young Italian student saves himself from a life as a galley slave by claiming to be a doctor. In Constantinople, refusing to convert to Islam, still a slave, he becomes half-astrologer, half-doctor to a wealthy pasha. So begins The White Castle by Orhan Pamuk (Carcanet).....

The student learns that he has a doppelg..ä..nger, a Turk who is his exact physical double. This man, his new master, the Hoja, is obsessed with science and the new European learning, which is beginning to enable the rationalist West to outstrip the Islamic East. Together, they plunge towards each other, learning everything the other knows. Gradually they merge, until they are indistinguishable, intermingled souls...

Now 38, Pamuk, the author of this remarkable fable, is one of Turkey's most celebrated — and widely read — younger novelists. Born and educated in Istanbul, he studied the English classics there — Milton, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Coleridge — at Robert College, the cosmopolitan American secular university. Fluent in English, Pamuk has been a writer-in-residence in the USA...

Nor is his background religious. "Not at all — I remember my grandfather singing atheistic songs". So the growth of fundamentalist Islam is something he views with discomfort? "We sit around in Istanbul, my friends and I, and ask ourselves if one day we ourselves will be harried, persecuted. Three weeks ago in Istanbul a writer, an Imam who had become an atheist, was shot dead. In Turkey writers are shot, can be shot dead. The human rights situtation is appalling. I defended Salman Rushdie's right to publish on the front page of Cumhuriyet. But Islamic fundamentalism is a fact of life, and a growing one."..

There are plenty of parallels between what has happened in Turkey's recent past and the lives of Pamuk's enigmatic fictional characters. By mastering Western science the Hoja gains favour with the young Sultan, predicting the end of a terrible plague by interpreting statistics and enforcing quarantine. The Sultan, playful and credulous (based on the young Mehmet IV who loved animals and hunting) is fascinated by the stories, inventions, the wisdom of the West; always, though, it is the Italian slave who is credited — and blamed — for the Hoja's skills. The Hoja grows to despise the oriental, fatalistic quality of the Turkish, the Islamic mind, becomes a fanatical devotee of science and the West...

Like Ataturk himself? "Oh yes — and like Kemal Ataturk the Hoja has a dark, Dostoevskian side. I often think of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk as a figure from Dostoevsky, his drinking, his black moods, his violent passions."....

The world of seventeenth-century Constantinople is, however, seen through modern, westernised eyes.....

"There's an element in me which enjoys the role of victim, wallowing in western orientalism — which I take great ironic delight in — that sense of looking through the eyes of others, seeing one's own culture as an elegant, charming, exquisite failure. All my novels are about the gulfs and complicities between East and West.....

In the past, you were either for or against — the West was paradise or decadent hell. I'm not so moralistic. My characters are victims and persecutors both. Ten years ago I was attacked for being unpolitical. Now the right attacks me for being irreligious."..

In The White Castle there is a vast engine of war the Hoja builds, on western principles, to gain greater favour with the Sultan in his war with the Poles. It is hated and feared by the rest of the army and flounders in the mud, a huge failure, precipitating the two men to exchange clothes and identities, the Hoja deserting to Italy...

This specific drama in the book serves as a metaphor for almost any conflict between cultures. "I hope the book is being read in Japan," Pamuk said. "They were once like us, the poor Turks: backward, with an old, proud traditional culture. But they changed, were able to change, become modern and successful, whereas we still have this feeling of failure and defeat. But, look, also you know it's a book about identity, a personal book about not being at the centre. Really, one doesn't care about the western perception of one's culture in the end. The same everyday Chekhovian dramas of ordinary life are being played out in Istanbul or Baghdad — the burning of flags, the demonstrations are such a small part."..

And disillusion? Would not the Hoja be disappointed, in the end, by the tawdry reality of the west? "No, no." Pamuk laughed. "That would be like Chekhov having one of the sisters come back from Moscow saying, 'Well, I've been there, it's not so great you know...' For Turks there is still this dream of being at the centre instead of on the periphery. It's part of our failure; Turkey which was once a great empire, a great culture, has fallen so far behind. It makes me sad, personally, and ashamed."..

Pamuk has been influenced by Borges, Calvino, Dino Buzatti, Landolfi and Svevo — so much so that reading the novel in English it is sometimes hard to remember it is not translated from the Italian...

The ironies abound like mirrors, each reflecting and distorting: the renegade Hoja writes books in Italy denouncing Islam and the Turks, predicting their further decline, while the Italian left behind retires to the Anatolian countryside to cultivate his garden, all desire to return home lost. He has become a potent symbol, to his former master, of why Turkey is doomed. Though never a formal convert to Islam his whole nature has accepted keyf, that mystical Islamic fatalism. Pamuk himself is not a wholehearted subscriber to this...

"I'm fascinated by the quietist, the Sufi tradition," he said. "But by temperament I'm always nervous, hectic, dissatisfied. But look, as well as these symbolic elements, it's mainly a tale of two lonely men, two solitary individuals, who teach each other all they know, how to read, how to write.'..

Success has come slowly to Pamuk. He had nothing published for the first 10 years of his writing career. He lived in Istanbul in retreat from the violent political atmosphere of Turkey in the Seventies and Eighties, when one could be shot in the streets for carrying the wrong newspaper. Ironically, now he is a bestselling author, everyone asks for his political opinions all the time...

The White Castle ..is an elegant and important meditation on East and West. Despite its slight length, it is philosophically and historically profound, and comparisons with Kafka and Calvino do not exaggerate; their seriousness, their delicacy and their subtlety are everywhere in evidence.....