TURKISH WRITER CAPTURES THE INTENSITY OF DESIRE

BY JUDY STONE

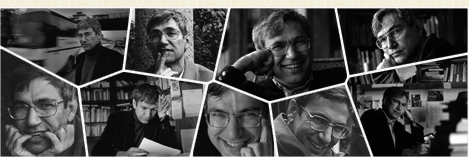

With an impish look behind his glasses, Orhan Pamuk, Turkey's leading author, talked about the playfulness in his latest novel, "The New Life," when he visited Berkeley recently.

"My book," the tall, lean writer says, "is my attempt at being visionary through the experience of love. It has a tongue-in-cheek quality about the effect of love on one's spirit. The intensity of desire is so overwhelming that the narrator is in a new world, in a new life. It's about maturing through love, reaching a higher level of consciousness."

The title is appropriated from Dante's "La Vita Nuova," Pamuk allows. "Dante's is an account of how he fell in love, along with autobiographical digressions about the effect of love." Although it's impossible to neatly summarize a Pamuk book, "The New Life" is also a meditation on the way literature can affect — or afflict — a nation.

"I read a book one day and my whole life was changed," Pamuk's 22-year-old narrator, Osman, declares at the outset. That book and the radiant Janan, his beloved raveling companion, are the stimuli that send him off on a series of terrifying, accident-prone, angel-haunted bus trips across a desolate landscape. Osman's goal is to discover the unknown author's vision of a new world. Janan's aim is to find Mehmet, her former lover, who disappears after being shot.

Never mind that we never learn exactly what Osman's mysterious book promises; we do understand that this life-changing book is as threatening as a Salman Rushdie manuscript to the book killers out there. Its "incandescent" light permeates the consciousness of the narrator even as he and Janan observe thousands of kisses and crashes in the B movies glimmering on the video screens of the buses on which they ride.

When Janan also disappears, Osman searches for the elusive Mehmet, whose father, Dr. Fine, has sent many spies to keep watch on his rebellious son and to murder readers of the book. Dr. Fine symbolizes the conservative Turks who resist subversive Western literary influences.

Although he may have mapped out his novel like a road movie, nothing is simple coming from the pen of Pamuk, whose work has been translated in 15 languages and who has been compared to Borges, Calvino and Proust. In two years, "The New Life" sold 200,000 copies in Turkey.

Does he see Janan (which means "soul mate" in Turkish) as the counterpart to Dante's Beatrice? "Yes," he says, vigorously ruffling his hair as if to shake out the explanations. "But Janan is less naive, less idealized. She is not an imaginary being in the vision of the lover. She is sitting next to him in long bus runs. They have fun together. On the other hand, the sexuality is also suppressed, as perhaps in Dante. What is different from Dante is that she has had someone else and the presence of Mehmet is felt very closely in the book."

Pamuk says that he and Dante "both have trouble with the religious life of their countries. In fact, my book was written more than two years ago, before the fundamentalists gained power. What the book depicts is the provincial anger, the fury that fundamentalists base their strategies on and grow with. In the eastern part of Turkey, the people are poor. They make only $400 a year."

The problems are exacerbated by the ongoing war against the Kurds. "The book conveys the terror of living in a country where everything is shaky, fast-moving, as if you are in one of those creaky old buses trying to watch B movies," he says.

Pamuk and his brother (who holds a Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley) were raised in a wealthy secular Istanbul household headed by his grandfather, who ran a factory and made a fortune building railways. The Pamuk home was a typical Ottoman household, with relatives on every floor. His grandmother, who taught him to read, also recited "almost atheistic" poems to him.

"In my childhood, religion was something that belonged to the poor and to servants. My grandmother used to mock them. Now with the rise of the fundamentalist movement, it's the revenge of the poor against the educated, Westernized Turks and their consumer-society life."

Pamuk has built a formidable reputation in Turkey since the 1982 publication of his first novel at age 30, the still untranslated "Cevdet Bey and His Sons." Today he says, almost crossly, "I'm tired of being a Turkish writer, in a sense. What I do is fiction. I sometimes feel I don't belong to any country. If I belong to a republic, I belong to a republic of literature.”

Former Chronicle film critic Judy Stone is author of 'Eye on the World: Conversations with International Film-makers.'